A full 150 years ago, on June 22, 1874, Dr. Andrew Taylor Still declared the founding of osteopathic medicine. Every day since that day, humanity has reaped the benefit of his meticulous study.

In conjunction with the best of modern medicine, the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine (LECOM) unabashedly carries the torch of Dr. Still’s revolutionary whole body health philosophy into the 21st Century.

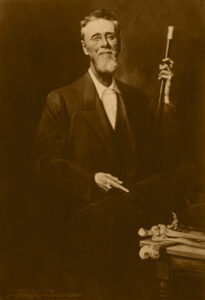

MAN OF VISION – Andrew Taylor Still

My father was a progressive farmer, and was always ready to lay aside an old plough if he could replace it with one better constructed for its work. All through life, I have ever been ready to buy a better plough.

~Andrew Taylor Still

Andrew Taylor Still was born the third of nine children to Abram and Martha Still in a log cabin in Lee County, Virginia in 1828. He was the son of a traveling Methodist minister who was also a practicing physician. As a youngster, Still admired the medical work of his father and he was nourished in the love of medicine. Determined to follow in the path set by his father – as a physician, the young Still studied medicine. In later years, he served as an apprentice under his father. Still became a licensed Doctor of Medicine just before the outbreak of the Civil War in 1860. He went on to serve in the United States Army as a surgeon during that period.

Dr. Still enlisted in the Union ranks, serving as a hospital steward in the 9th Kansas Cavalry, finally advancing to Major in the 21st Kansas Militia. In October of 1864, Dr. Still’s unit was involved in a skirmish outside of Kansas City as they attempted to repel the Confederate troops marching on the city. Dr. Still worked as a battlefield doctor following the troops of Army General Sterling Price. While working as a Civil War physician, Dr. Still began to observe that orthodox medical practices of the day often were ineffective and frequently harmful. In his autobiography, Dr. Still described his observations of doctors who dosed sick or injured men with liquor and opium that did little or nothing to treat their ailments and often created addicts and drunks. He noted further that during the Civil War, in those portions of the states of Missouri and Kansas where doctors were shut out, the children did not die.

In the years shortly following the ravages of the war, Dr. Still continued to practice conventional frontier medicine. Toward the latter part of his engagement, Dr. Still received orders to disband the regiment and to return to his home.

Upon his arrival at his homestead in 1864, Dr. Still faced a critical personal calamity. Earlier that year, a frenzied epidemic of spinal meningitis had swept through the area. He found his wife and all three of his children had contracted the disease. All three of his children perished. He had already lost his first wife to complications during childbirth; a month after the epidemic, the daughter born to his second wife, Mary Elvira Turner, died of pneumonia. His inability to save his family, paired with his dire and dismal experiences as a Civil War doctor, prompted Dr. Still to repudiate most of that which he had learned about medicine and to seek out fresh and improved methods of treatment.

During his family’s illness, Dr. Still had been without answers and all remedy had been useless. Without the power to have helped them and as a physician, Dr. Still was left to feel distressed and anguished. The common apparatus available to a frontier doctor during those years were such therapies as morphine, laudanum, and mercury. Dr. Still thought these intended remedies were not at all restorative and further, he believed them to prove more injurious than curative.

Drawing from his observations in the battlefield, Dr. Still was quoted as saying “I began to see during the Civil War, in that part of the states of Missouri and Kansas where the doctors were shut out, the children did not die.”

After the loss of his family, Dr. Still dedicated his life’s work to the development of a process of medicine that would promote healing in his patients. He accomplished this objective by revisiting the very essence of anatomy and physiology. Dr. Still examined existing medical principles and he parsed the formation of medical theories. “I have no desire to be a cat, which walks so lightly that it never creates a disturbance,” the doctor asserted.

Dr. Still became predominantly interested in examining circulation and nerve flow to maintain health. He advanced and cultivated a philosophy of medicine based upon principles first put forth by Hippocrates, the father of medicine. This new philosophy focused upon the unity of all body parts and it formed the underpinning of Dr. Still’s concept of “wellness.” His was a concept that identified the musculoskeletal system as constituting a fundamental element of health.

Dr. Still recognized the ability of the human body to heal itself and he stressed preventive medicine, eating properly, and keeping fit. During the latter part of the 19th century, a germ theory of disease was growing in popularity and it was being furthered in general application throughout the standard medical communities. It was during this time that Dr. Still rejected such scientific research and he openly opposed the use of drugs and vaccination.

He concluded that “disease is the result of anatomical abnormalities followed by physiological discord.” His study centered upon the belief that by correcting problems within the structure of the body and by restoring the normal and regular blood supply to the body, the natural ability of the body would function to heal and restore itself. Dr. Still became so adept in the manipulation of the musculoskeletal system that he garnered a reputation for being the “Lightning Bonesetter” and he went so far as to promote himself in that fashion on cards and posters. Relentless in the advancement of this process of practice, the doctor became more convinced of its application as it developed in reputation and success.

Dr. Still was intractable in his pursuit of this medical triumph stating, “You find that all men are successes or failures. Success is the stamp of truth. I will say all men who fail to place their feet on the dome of facts do so by not sieving all truth and throwing the faulty to one side.”

So convinced was he of the validity of this new technique, he would spend the rest of his life in the perfecting of the mission. Dr. Still named this practice of medicine “osteopathy” to distinguish it from “allopathic” medicine. As a pioneer of his time, Dr. Still was one of the first to examine the characteristics of good health in such a manner that he could more thoroughly comprehend the process of disease and illness. For nearly twenty years, Dr. Still alternately practiced and gave instruction in his manipulation methods; and throughout those two decades, thousands of persons were restored to health. Dr. Still found the process of distribution too sluggish to suit his motivations, and he moved to establish a school so that he and his sons could educate and train a number of physicians at the same time.

After nearly twenty years of practice, Dr. Still settled in Kirksville, Missouri. With his colleague, William Smith, a Scottish MD, Dr. Still founded the first school of osteopathy. The American School of Osteopathy opened in 1892 approximately 80 miles north of Columbia, Missouri. Dr. Smith agreed to teach anatomy in exchange for learning osteopathy. The first class of osteopathy included 15 students with one-third of them, women. As such, osteopathic medicine was born in America and it became a distinctive form of American medical care. In 1874, Andrew Taylor Still, MD, graduated his first class of Osteopaths and the new field of medicine would take the world into a new era of healthcare.